| Christmas at Ranong

Burmese refugees' in Southern Thailand

Duncan MacLaren coordinates Australian Catholic University's Refugee Program on the Thai-Burma border and lectures in Catholic Approaches to Humanitarian and Development Work.

|

I am in Ranong and cannot sleep. For the geographically challenged, think Isthmus of Kra in southern Thailand at the point where Burma ends and Muslim Thailand begins, going down to Malaysia. I am in the Marist Fathers' house. |

A young Burmese boy of nine who was found abandoned in the forest and then cared for by a poor Burmese family with support from the Marists plays with the priest's big toe. A young girl of 15 dressed in a school uniform, her hair cut short like a Thai to escape abduction, is too young for the ACU online diploma but asks to attend anyway to learn, just to be part of the dream of having higher education. |

| TOP |

| West Papuan torture

Sr Susan Connolly RSJ

Susan Connelly is a western Sydney-based Sister of St Joseph who for many years has been the prime mover in the advocacy work of the Mary MacKillop East Timor Mission.

|

Some weeks ago there were reports in the media concerning the torture of West Papuans. Graphic images were displayed and cries of suffering could be heard. One of the reasons is the impunity that Indonesia enjoys, shown in the complete lack of responsibility taken for what happened in Timor-Leste between 1974 and 1999. |

There were some attempts to evade international scrutiny in the establishment of an ad hoc Human Rights Court and a Truth and Friendship Commission, neither of which brought anyone to justice. It is criminal that similar treatment is being suffered by West Papuans; criminal on the part of Indonesia whose military machine still considers itself above human decency, and criminal on the part of Indonesia’s neighbours, including Australia. |

| TOP |

The ticking bomb of lay involvement

Sr Joan Chittister OSB

Posted in National Catholic Register, USA, , Oct 18, 2010 |

Ticking time bombs are among the world’s most dangerous weapons. Most of them are too small to see at first glance. Most of them are easy to make. You can plant a number of them at one time. They can do a great deal of damage, however small. 1 Reread annually a summary of the second Vatican Council reforms. 2 Commit yourself to interfaith bridge building. 3 Be open to a changing position of the church on gays and women. 4 Learn more in the first four years of your priesthood than you did in the recent [seminary trainings]. |

5 Prepare your homilies with one hand on the Bible and the other on (with) the daily newspaper. 6 Work with people rather than imposing a top-down strategy. 7 Respect the role of the laity in an evolving Church. 8 Build upon personal spirituality by a growing concern for social justice. 9 Store your seminary notes in an inaccessible place. 10 Remember that an unquestioning “company man” in all professions, even the priesthood, sacrifices creative energy. Seminarians: attention. |

| TOP |

A senseless war begins its 10th year

Michael Moore. Thursday, October 7th, 2010 Michael Moore Michael Moore is an activist, author, and filmmaker. See more of his work at his website MichaelMoore.com

|

My Fellow Americans |

In fact, the only reason I can see is that this war is putting billions of profits into the pockets of defense contractors. Is that a reason to stay, so Halliburton can post a larger profit this quarter? It is time for me to bring our troops home -- right now. Not one more American needs to die. Their deaths do not make us safer and they do not bring democracy to Afghanistan. (End of speech, as transcribed by Michael Moore) |

| TOP |

Communites confront flood fallout

Ben Fraser is an aid worker who recently returned from flood-devastated Pakistan. |

The war weary population of Shangla District in the restive frontier region of northern Pakistan have little time for self pity. Their response to Pakistan's colossal flood disaster, aptly likened by UN Secretary-General Ban ki Moon to a 'slow motion tsunami', was decisive, the antithesis of victimhood. Consequently the dollars barely trickled in, with many governments failing to rapidly allocate emergency funding so sorely needed. The response in the US was indicative of this sluggishness: by 27 August a mere $12 million had been raised by US NGOs compared with $500 million for the Haiti earthquake over the same period. |

Amid the horror and gloom there have been moments of inspiration in the flood crisis that have largely gone unreported. What Pakistan's 'super flood' has taken will be hard to regain. Beneath the diminishing flood tide are millions of homes and vast tracts of agricultural land sodden and spoiled. Inevitably in such circumstances it is the poor who must battle on with hope as their best asset. |

| TOP |

Time for detention reform

Kerry Murphy is a partner with the specialist immigration law firm D'Ambra Murphy Lawyers. |

The recent tragic death of a man in Villawood Detention Centre has again raised questions about the need for Australia's harmful detention policy. Freezing processing, as occurred in April for Afghans and Sri Lankans, adds to the uncertainty and unfairness while also prolonging detention. There are three different systems used by Australian Immigration officers for assessing refugee cases. The fairest process provides for a strict legal assessment, an interview, and independent review by the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT). There are avenues of appeal to the courts on errors of law. This is the process for protection visa applicants, most of whom are living in the community and are not in detention. The second process is a less transparent system with no real independent review. People arriving by boat or plane without a visa must be detained. If sent to Christmas Island, they are classified as 'offshore entry persons' which means that they can only make an application for refugee status if the Minister allows them. They will be interviewed but must stay in detention throughout the process. This system has less accountability than the onshore processing system and is designed to keep claimants away from the courts. The third system applies to those who are offshore, maybe in camps in Africa or the suburbs of Damascus or Amman. This system does not even require an interview and most of these cases are refused on the papers. Most asylum seekers in detention are in the second system. Very few detainees get the benefit of the more scrutinised 'onshore' system. This creates anxiety for people who wonder why they are being treated differently. |

This fear is inevitable, regardless of the quality of the decision-makers, because the assessment system is flawed.

|

| TOP |

U.S. havoc in Iraq From the article by Adil E. Shamoo a senior analyst at Foreign Policy In Focus, and a professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine

|

“Iraq has between twenty-five and fifty percent unemployment, a dysfunctional parliament, rampant disease, an epidemic of mental illness, and sprawling slums. The killing of innocent people has become part of daily life. What a havoc the United States has wreaked in Iraq. “For the past few decades, prior to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the percentage of the urban population living in slums in Iraq hovered just below 20 percent. Today, that percentage has risen to 53 percent: 11 million of the 19 million total urban dwellers. In the past decade, most countries have made progress toward reducing slum dwellers. But Iraq has gone rapidly and dangerously in the opposite direction. |

“If the United States had an unemployment rate of 25-50 percent and 121 million people living in slums, riots would ensue, the military would take over, and democracy would evaporate. So why are people in the United States not concerned and saddened by the conditions in Iraq?Because most people in the United States do not know what happened in Iraq and what is happening there now. Our government, including the current administration, looks the other way and perpetuates the myth that life has improved in post-invasion Iraq. Our major news media reinforces this message.” |

| TOP |

|

| TOP |

Asylum seekers:

Greg Foyster

Greg Foyster is a freelance journalist who has written for The Age, The Big Issue, Crikey and New Matilda. |

While politicians search for islands to house 'boat people', asylum seekers living in the Australian community face an accommodation crisis of a different kind — homelessness. Hard data on the problem is scarce because the Australian Bureau of Statistics doesn't track the number of homeless asylum seekers in the community. But refugee agencies across the country estimate that the rate of homelessness among in-community asylum seekers is extraordinarily high. A spokesperson for the Refugee Claimants Support Centre in Queensland says between 60 and 70 per cent of the agency's clients 'need some sort of assistance with obtaining or maintaining accommodation'. Prabha Gulati, director of the Asylum Seekers Centre of NSW, estimates one in four asylum seekers her agency helps are 'homeless or in danger of imminent homelessness'. A July 2009 survey found that 78 per cent of asylum seekers on the Asylum Seeker Assistance Scheme (ASAS) in Victoria met the government definition for homelessness. Although some asylum seekers have slept on the streets, many have also experienced other forms of unsafe and insecure accommodation, such as crashing at friends' places, staying at boarding houses or sleeping at churches, temples and mosques. According to casework data from the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, an individual or family seeking asylum will move an average of eight times in an attempt to source appropriate and sustainable accommodation. With few rental references and complex visas, asylum seekers have trouble accessing the private rental market. They are also ineligible for most public housing and don't fit within the homelessness welfare system, which is designed to cater for people with different needs, such as substance dependence. And although asylum seekers are technically eligible for 'transitional' accommodation, they are frequently refused due to lack of income. Even the Federal Government overlooks homeless asylum seekers. The Labor Government White Paper on homelessness, The Road Home, is supposed to set the strategic agenda for reducing homelessness in Australia for the next decade. Asylum seekers are not mentioned in the paper. Nor is there any legislative framework mandating housing for asylum seekers in Australia. All these points are raised in Australia's Hidden Homeless, a new research project into the accommodation crisis among asylum seekers in the community. The report is the work of Hotham Mission Asylum Seeker Project (ASP) with financial backing from a charitable trust. Only a charity could have drawn attention to this issue because refugee agencies and church groups bear the burden of housing homeless asylum seekers. These agencies rely on donations and philanthropic organisations to keep afloat. Government funding is minimal or non-existent. |

A good example is Sanctuary House, an accommodation facility in Melbourne for male asylum seekers at risk of homelessness. Dr Andrew Curtis, general manager of strategic development and sustainability at Baptcare, says 'we have no federal or state funding for this facility at all'. In the UK, Sweden and Canada, housing for asylum seekers living in the community is government funded and managed through the country's immigration department or at a local level. Governments acknowledge that they have a legal and moral responsibility to provide services to asylum seekers claiming protection. Australia's Hidden Homeless quotes a spokesperson from the Swedish Migration Board: As a signatory to the 1951 Convention, the government has a responsibility to ensure that people are mentally as strong as possible to consider their future in or outside Sweden ... if you've signed the Convention, then you have a responsibility not just to provide protection when and if this is determined, but during the determination process ... you need to give people a decent life while you are processing their claim ... and the lowest level is providing food and bed. Australia has also signed the Convention, though you'd have trouble squeezing that quote out of the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. At the moment, the political focus in our country is on 'boat people', detention centres and offshore processing. Asylum seekers who arrive by plane and live lawfully in the community are off the agenda. Yet historically, plane arrivals make up the majority of asylum seekers. And providing housing to this group is much cheaper and simpler than building offshore processing centres for those coming by sea. Caz Coleman, director of Hotham Mission ASP, says Australia's Hidden Homeless puts forward a cost-effective model 'with a per bed price of approximately $31.30 for a single asylum seeker living alone and less than $12 per day for asylum seekers living in shared housing'. Every day, Australians face north and scan the horizon. Has another boat arrived? But if our politicians and journalists want to see asylum seekers living in poor conditions, they need to look closer to home. We have plenty of destitute asylum seekers right here, and they're being ignored. Posted Aug 19, 2010 |

| TOP |

I am every asylum seeker

Greg Foyster

Greg Foyster is a freelance journalist who has written for The Age, The Big Issue, Crikey and New Matilda. |

I was born in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. I was born in Kashmir, between India and Pakistan. I was born in Iran. I was born in Iraq. I was born in Sri Lanka. I worked as an architect, building up my business. I worked as a negotiator, liaising with the government. I worked as an engineer. I worked as a veterinarian. I worked as an accountant. I am a member of the Hazara ethnic group. I am opposed to the government's occupation of Kashmir. I am a firm believer in women's rights. I am a whistleblower for government corruption. I am an ethnic Tamil. I was held down while I watched my father beaten to death. I was kidnapped by the government and taken to an interrogation room. I was knocked out with the butt of a rifle. I was shot three times. I was arrested and put in a camp. They kept me in a solitary cell for four days without food or water. They drove a nail through my thumb and put fresh chilli in the wound. They beat the soles of my feet with canes. They pulled out my fingernails. They placed a metal roller on my shins and applied pressure until I screamed. I bribed a guard to help me escape in the middle of the night. I fled through the mountains and a farmer smuggled me across the border. I hid underground for five months. I sold my property and used the money for a plane ticket. I cut a hole in the wire fence and crawled through the jungle to a safehouse. I got on the first boat I could, wherever it was going. I paid a man $7000 to take me somewhere safe, but he left with my money. I spent months in Indonesia hiding in the forest. I was dumped in the middle of the ocean and had to swim to shore. I arrived on Ashmore Reef and collapsed from thirst and heat exhaustion. I was so relieved to be in Australia! I was happy to be safe from the militia! I was alive, I was overjoyed, I was finally free! |

I was then locked up on Christmas Island for three years without a lawyer. I was put behind bars and razor wire in the middle of the desert. I was called by a number not a name. I was kept in an isolation cell. I was beaten and abused by the guards. Why am I locked up if I haven't committed a crime? How can I be in prison without a trial? Why can't they treat me like a human being? Why am I kept here all alone? Why haven't I been told when this will end? I am depressed and have constant headaches. I am frightened and wake up screaming. I am losing my mind. I have sewn my lips together. I have tried to kill myself. I didn't want to be a refugee. I didn't want to come to your country. I didn't want to leave my family. I didn't want to lose my house. I didn't want to have to start again. I am not here to get rich. I am not here to receive charity. I am not here to steal your job. I am not here to cheat the system. I am not here by choice. I am here because otherwise I would be dead. I am here because the militia threatened to kill me and my family. I am here because I was shot. I am here because my house was burned down. I am here because I have nowhere else to go. I was born in a dangerous land. I was persecuted for who I am and what I believe. I was tortured in an interrogation room. I was dumped in the ocean. I was locked up in detention. I am an asylum seeker, every asylum seeker, and this is my story. I am not a 'queue jumper'. I am not an 'illegal arrival'. I am not a 'political issue'. I am a human being. Please treat me like one. Posted Aug 19, 2010 |

| TOP |

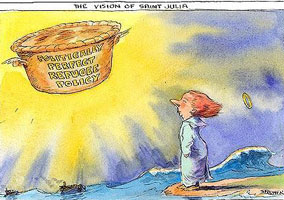

Gillard's unfair 'solution' David Manne

David Manne is executive director of the Refugee & Immigration Legal Centre. This article appeared in 'The National Times', Jul 15, 2010

|

A strange bipartisanship now hangs over asylum seeker boat arrivals. On becoming Prime Minister, Julia Gillard confronted two stark questions on asylum seekers, an immediate domestic political issue and a profound question of policy and principle with implications well beyond our borders and the imminent election. She has sought to answer the political question with a proposal to stop the boats. Time will tell whether her promise has worked. On the policy question, the plan - sold as a fresh "vision" - involves exiling asylum seekers who arrive by boat to another country in our region for ''processing''. Whether that be East Timor or elsewhere, the policy is unfair and unworkable in equal measure. It is incapable of realising the worthy ambition of developing a "sustainable, effective regional protection framework". Cutting through the political jousting and attempts to distinguish the ''Dili Solution'' from the Howard government's Pacific Solution, the reality is that the policies of the government and the opposition have converged. A strange bipartisanship now hangs over asylum seeker boat arrivals. At the core of the policies of both parties is the creation of an offshore processing centre. With the East Timorese Parliament's rejection this week of the plan, both parties are now on equal footing: neither can say where the ''processing centre'' will be. Much focus has been on whether Dili is the right place for the plan, rather than whether it is the right policy, wherever the place. So what are the broader implications of offshore processing in the region under what appears to be a repackaged Pacific Solution? As to fairness, the Prime Minister's proposal risks violating Australia's international legal obligations under the Refugees Convention, whereby a person who arrives here should be able to seek and be guaranteed protection from persecution on our soil. Instead, the plan seeks to circumvent these obligations by deflecting responsibilities to another country in the region. This strategy was a foundation of the Pacific Solution. As the plan stands, it gives only one guarantee: that boat arrivals in Australia will be exiled to an unknown regional neighbour. Beyond that, all is unknown. How will people be housed and treated, and will they be detained? How are claims to be processed, and by whom? What safeguards against unfairness will apply? What role, if any, would the UN refugee agency play? Where and when would those found to be refugees be resettled? Experience in Nauru and Papua New Guinea shows that people were detained in remote, poor conditions, subject to a flawed and unfair process without proper safeguards, and were left in limbo for years. Many suffered severe psychological and physical damage.

|

The government has promised a big, bold policy innovation claiming to offer long-term solutions regarding refugees, while not returning us to the inhumanity of the Pacific Solution. It bears the onus of telling us how and why. Yet no real explanation has been provided as to why we should expect a different outcome from the past. This policy runs the risk of being no more than a rebadged Pacific Solution. The government has made much of the fact that the processing centre would be housed in a country that has signed the Refugees Convention, such as East Timor. But this distinction is largely illusory and irrelevant. Whether located in Nauru (a non-signatory) or East Timor, what real difference this would make remains unexplained. Nauru's sudden indication that it would consider signing the Refugees Convention exposes the hollowness of the distinction, and the dangers of this plan turning the convention into a cynical marketing tool for potential client states of Australia. An offshore processing centre is not a regional solution of itself. The many challenges posed by asylum seekers in the region require development of a regional co-operation framework which, if properly constructed, could better manage these complexities. But it needs to be forged on a genuine partnership between states in which all players co-operate on agreed principles for the humane treatment and improved outcomes of those fleeing brutality. It cannot work based on simplistic solutions such as an offshore processing centre, where Australia's responsibilities are deflected on to our more vulnerable neighbours, for domestic political benefit. East Timorese concerns about the destabilising effects on their country if it hosts a huge human warehouse, are likely to be shared wherever the plan is exported. The reality is that options for resettlement of the more than 10 million refugees worldwide are extremely limited, and may become moreso where Australia's responsibilities are deflected. Without guarantees, recognised refugees are almost certain to languish in limbo. The Pacific Solution revealed great reluctance by other states to assume Australia's responsibilities. The policies of both parties send us back to a future where vulnerable people seeking our help are cast into indefinite exile with the knowledge that many will be crushed in the process. While policies should discourage people risking their lives on boats by, for example, increasing resettlement places from Indonesia and elsewhere, they should never punish such innocent people, conscious of the lasting harm it can cause. We should be showing leadership with policies that limit suffering rather than ones which compound it. Posted Jul 16, 2010 |

| TOP |

Unlocking Sex Trafficking Somaly Mam to speak in Sydney, Jun 22, 2010 |

Somaly Mam was honoured as one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people of 2009. At the age of 12 she was trafficked into the sex trade in Cambodia where she was forced to work for years in a brothel along with other children and brutally tortured and raped on a daily basis. Today Somaly Mam is co-founder of AFESIP, a non-government organisation in Cambodia ('acting for women in distressing situations') which employs a holistic approach that ensures victims not only escape their plight but have the emotional and economic strength to face the future with hope. With the launch of the Somaly Mam Foundation in 2007, Somaly has established a funding vehicle to support anti-trafficking organisations and to provide victims with a platform from which their voices can be heard around the world. |

Come and listen to her riveting story of courage, determination at all odds and hope for the future. On her very first Australian visit she has been invited to be a guest speaker at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and share her inspirational story of survival and strength. She is speaking on Tue, Jun 22, 2010, at 11 am, at UTS’, 745 Harris St, Ultimo (Sydney). Somaly Mam's visit is sponsored by 'Project Futures'.

|

| TOP |

Self harm among asylum seekers

Recently returned from Christmas Island Fr Jim Carty SM has been quoted in an article by Ben Packham in Victoria's 'Herald Sun'. Here is Packham's article, Jun 03, 2010...

|

'Self-harm increasing among asylum seekers in detention centres'Concerns are raised over the mental health of asylum seekers in detention with self-harm incidents doubling. Asylum seekers are once again resorting to self-harm in detention centres amid overcrowding and stalled refugee claims. The Herald Sun has learnt that at least 17 immigration detainees injured themselves or attempted suicide in the past 11 months - almost twice the number of incidents of the previous year. Many more detainees are suffering from mental illness, with regular transfers from Christmas Island to the mainland for those needing specialist treatment. Self-harm by detainees sparked concerns over mandatory detention under the Howard Government, and Kevin Rudd's pledge to be "tough but humane" in his own treatment of asylum seekers. Catholic priest Jim Carty, who recently returned from nine weeks on Christmas Island, said he knew of at least one detainee who tried to hang himself there. He also met a Tamil man with eight large cigarette burns on his arm. "Each burn marked the passage of another month. It was a sort of reminder to him of the situation he was in," Father Carty said. The Herald Sun has also heard of detainees cutting themselves, and of a man destined for deportation who drank bleach and shampoo. According to the Department of Immigration, there have been 17 self-harm incidents since July; 10 in 2008-09 and 12 in 2007-08. |

A department spokesman said: "Some people in immigration detention arrive with pre-existing mental health issues while others can develop these as a result of uncertainty around their immigration status." Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry said he was concerned the recent freeze on processing of Afghan and Sri Lankan asylum seekers would lead to more mental anguish among detainees. "Indefinite detention is definitely a health hazard," the psychiatry professor said, adding the remoteness of detention centres made it impossible to provide adequate mental health care. "That's my big objection to the Pacific Solution or the desert solution or the Christmas Island solution - I mean, what is the reason for it?" Prof Louise Newman, chair of an independent advisory committee on detainee health, said many asylum seekers were "profoundly depressed" as a result of their situation. "It's of great concern that Christmas Island is as crowded as it has been," Prof Newman said. "I would hope that we look back at the problems that happened before and realise that mandatory detention in remote areas is not an easy thing to run in a way that does not damage people, particularly children and young people." |

| TOP |

A letter to

Marist Provincial, Fr Paul Cooney SM, has forwarded this suggested letter from the Leaders of Religious Institutes of Australia. It is likely to be topical into 2010... |

Mr Kevin Rudd Dear Mr Rudd, The current situation regarding the boatload of Sri Lankan asylum seekers moored off the coast of Indonesia is particularly worrying. As you are no doubt aware around 250,000 internally displaced Tamils have been, for the past 5 months, segregated into camps in Sri Lanka with extremely poor facilities and limited access to aid from NGOs. Reports indicate increasing levels of desperation when faced with water shortages, sickness and limited food supplies. The looming monsoon season is an additional source of anxiety. Such desperation is always a “push” factor when it comes to people making risky escapes from intolerable situations. In recent days we have seen just how desperate people can be. Few would deny that the Sri Lankan Tamils are being persecuted, that their freedom is curtailed and that, in many cases, their lives are in danger. Returning the recent boatload of Sri Lankan asylum seekers to Indonesia places legitimate asylum seekers at the mercy of a poor country with few resources, already over-stretched trying to deal with hundreds of abandoned asylum seekers eking out a tenuous existence in Indonesian coastal towns. Article 33 of the Refugee Convention of 1951 says: No Contracting State shall expel or return …a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. |

Australia is a signatory to that convention, Indonesia is not. We are country richly endowed with a strong political system, many resources, a harmonious, multicultural population and considerable wealth. We can afford to be generous, welcoming and hospitable. From a global perspective we accept very few asylum seekers. This year we have received around 1500 boat arrivals, in comparison with a country such as Italy which, in 2008, took in 36,000. Taking a stand against people smugglers is a laudable pursuit but not at the expense of desperate people fleeing injustice. The crisis is not so great that we need to turn people away. This is an opportunity for you and your government to make a stand against those who stir up xenophobia, pedal panic and oppose the rights of all people to seek asylum when faced with persecution. What is needed is for you, Senator Evans and the government to resist pressures for more draconian responses to asylum seekers and continue with humane reforms to our asylum and refugee policies so that they comply with the standards set by international human rights treaties and measure up to the Australian values of compassion, “a fair go” and hospitality. Your government is to be congratulated on the important changes you have made to the situation of refugees and asylum seekers coming to Australia. The abolition of the temporary protection visa, the closing down of Manus Island and Nauru and the elimination of charges for stays in detention centres have transformed the lives of people seeking asylum in our country. It would be a tragedy if these positive changes were to be undermined by an over-reaction to those accusing your government of being “soft” on asylum seekers. Yours sincerely... |

| TOP |

| TOP |

Stop attacks on Karen civilians

Statement from ten Karen (Burmese) communities worldwide |

Karen communities worldwide Karen communities in ten countries are joining forces for a global day of action on Tuesday, Mar 09, calling on the international community to take action to stop new attacks by the Burmese Army against Karen civilians. Since mid January more than two thousand civilians have been forced to flee new attacks.

Karen communities call for immediate practical action to stop the attacks.

Karen people have been under attack for more than sixty years. The new wave of attacks is linked to the Burmese dictatorship’s fake elections due later this year. The dictatorship is trying to crush all resistance forces to their rule. They are following the doctrine of the Burmese Army: ‘One Blood, One Voice, One Command’. The new constitution drafted by the dictatorship guarantees no rights or protection to ethnic nationalities. In fact, it is a death sentence to ethnic diversity in Burma. The international community must stop ignoring what is happening to ethnic peoples in Burma. |

We, the Karen Communities Worldwide, desire genuine democracy, peace and national reconciliation, but not military threats and attacks by the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) army to destroy our homeland and our dreams for a peaceful federal Burma. Karen Communities in the United Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, Germany, Canada, the United States, Australia, Japan, Malaysia and Korea are coordinating the day of action, which is supported by people from Burma and human rights groups. Released Mar 09, 2010 Contacts: UK Australia Canada Germany Norway USA Korea |

| TOP |

Christmas Island ministry Fr Jim Carty sets out to accompany asylum seekers...

|

Fr Jim Carty SM has commenced a three-month period as pastor of Christmas Island. Famous for its Immigration Detention Centre, the island is ‘home’ for 1,700 asylum seekers and their families in a facility designed to accommodate 800. Temporary ‘dongas’ and tents provide shelter for the overflow numbers. Having completed an eight-year directorship of Sydney’s ‘House of Welcome’ for asylum seekers and refugees, Fr Jim plans to be ‘a listener and a presence’ for the IDC residents. ‘People locked away in a time of transition and uncertainty and fear are often very fragile’, says Fr Jim. ‘They need a special kind of support and accompaniment. Many have suffered severe trauma and I will need to be careful not to touch on any triggers which will reactivate these traumas.’ Christmas Island is one of Australia’s offshore territories which have been ‘excised’ from legal opportunities for asylum seekers and refugees on the mainland.

|

Fr Jim comments, ‘Whilst the Rudd government has shown a more caring attitude towards asylum seekers through the abolition of the Temporary Protection Visa with its terrible uncertainty, it has continued with Howard’s excision policy. This means that asylum seekers have no access to the Australian legal system as we know it. Some asylum seekers have been granted the 866 temporary visa while others have been returned to their native countries. Most are here because they have simply fled for fear of their lives not especially because they wan ted to come to Australia.’ ‘There are a numbers of Catholics amongst the Tamil population of Christmas Island’s detention centre’, he said, ‘and I will be available to offer Mass at the centre for them and others who wish to come. Tamils, Afghanis and Burmese are amongst the main groups there. Fortunately families live in a special compound outside the centre.’ Fr Jim returns from Christmas Island after Easter. [Posted Jan 2010] |

| TOP |

The Darfur of

Jim Pollard writes for Bangkok's 'The Nation', Dec 08, 2009, on the plight of Burmese refugees continuing to stream into Thailand...

|

Thailand has been hit by the negative impacts from wars and civil strife in neighbouring countries for years, and that pattern shows no sign of ending anytime soon. Waves of refugees arrived following the end of the war in Vietnam in 1975 and the advent of communist governments there and in Laos and Cambodia. The situation worsened when hundreds of thousands of Cambodians poured over the eastern border in 1979 after the Vietnamese army swept the horrific Khmer Rouge regime from power in Phnom Penh. The humanitarian crisis that suddenly swamped Sa Kaew province dragged on for over a decade before a peace settlement in Paris opened the door for Cambodian refugees to return home in the early 90s as a UN peacekeeping force arrived to oversee a much-touted election. In the midst of that high-profile saga, a much smaller influx of refugees crossed into northern Thailand from eastern Burma. About 10,000 mainly ethnic Karen fled into Tak province after clashes in their home state in 1984. Members of a committee of international groups supporting Indochinese refugees agreed to go to Mae Sot to help deal with the Burmese influx. Few thought the problem would last. However, massive rallies against the Ne Win dictatorship in Rangoon in 1988 led to a bloody crackdown and an even more brutal military regime, whose methods have slowly transformed eastern Burma - if not the entire country - into another humanitarian tragedy. The scale of the trauma flared in the mid-90s when the junta reinforced its military campaign against ethnic armies on its eastern frontier. The fall of Manerplaw and other rebel bases in early 1995 was followed by vast forced relocations of villages and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. Thailand saw a huge influx of refugees. In 1994, there were 80,000 refugees in 30 small camps. But the massive and ruthless relocation of villagers in Karen state - who faced summary execution, forced labour and portering (often through minefields) - spurred a continued exodus to Thailand. Cross-border raids on some camps - seen as harbouring rebel fighters - forced Thai authorities to consolidate the camps in areas less vulnerable to attack. By mid-1997 there were 115,000 refugees in nine camps and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) was invited to provide protection services (as Thailand has never signed the UN Convention on Refugees). The gradual militarisation and takeover of ethnic territory - and the serious risks and difficulty in reaching areas targeted for suppression by the Tatmadaw (Burmese Army) has meant the crisis in eastern Burma has been little reported by both the Thai and international media. But the chaos and brutality persists. The Thailand Burma Border Consortium (TBBC), the biggest of about 20 NGOs providing services to refugees in border camps, run by the Ministry of Interior and refugee committees, has been monitoring the crisis zone for years. It says more than 3,500 villages and hiding sites in eastern Burma have been destroyed or forcibly relocated since 1996, including 120 communities between August 2008 and July 2009. "The scale of displaced villages is comparable to Darfur and has been recognised as the strongest single indicator of crimes against humanity in eastern Burma. At least 75,000 people were forced to leave their homes this... |

past year, and more than half a million remain internally displaced," it said in a recent statement. "The highest rates of recent displacement were reported in northern Karen areas and southern Shan State. Almost 60,000 Karen are hiding in the mountains of Kyaukgyi, Thandaung and Papun townships, and a third of these fled from artillery attacks or the threat of Burmese Army patrols during the past year. "Similarly, nearly 20,000 civilians from 30 Shan villages were forcibly relocated by the Burmese Army in retaliation for Shan State Army-South (SSA-S) operations in Laikha, Mong Kung and Keh Si townships." The relentless repression and deliberate targeting of civilians - under the notorious "Four Cuts" policy to cut off food, funds, information and support to the rebels - has reached a point where eastern Burma is now seen as Southeast Asia's "new Killing Fields". Calls for Burma's top generals to be dragged before an international court for crimes against humanity have grown louder and more frequent in recent years. But while former heads of Khmer Rouge face trial in Phnom Penh, the junta is happily ensconsed in its new capital Napyidaw, buttressed by billions from its gas pipeline to Thailand and unburdened by ties with China and Asean, both of which adhere to policies of non-interference. All of Burma's neighbours have suffered an influx of refugees, particularly ethnic groups oppressed by the Tatmadaw's violence. Thailand, at least, has wealthy allies, such as the US, Europe, Australia and Canada, who help care for the refugees. Some 16 foreign governments plus international aid groups support TBBC - a small, efficient outfit that manages nine camps from Kanchanaburi right up to Mae Hong Son. It provides food and shelter to about 150,000 refugees, an operation that cost about Bt1.2 billion (US$35 million) last year. Over the past five years more than 50,000 refugees have been resettled abroad, mainly in the US, but a similar number has flooded in to replace them. The Interior Ministry is interviewing these recent arrivals to determine if they are genuine refugees or opportunists seeking a new life in the West. TBBC executive director Jack Dunford has the daunting task of getting funds from international donors, who have been calling for Thailand to allow the refugees to work and be more self-reliant. Moves are slowly being made in that direction with the help of UNHCR and IOM. TBBC has faced tough times in recent years, with the price of rice soaring in 2008 and a push by some donors to give more aid directly into Burma, which receives little humanitarian assistance because of the onerous restrictions it places on aid groups. Small rises in three uncontrollable factors - exchange rates, the price of rice and refugee numbers - "can suddenly add millions" to their costs, but there is also huge international goodwill. "It is remarkable that we've been able to do what we've done for 25 years and that is thanks to the incredible support we've had," Dunford said. The Englishman said, after a quarter of a century, he and his colleagues have much to be proud of. "We have never in 25 years failed to give the refugees a full food basket, whereas all over the world refugees are getting partial rations." |

| TOP |

Australians are xenophobic

Julian Burnside QC is a Melbourne-based barrister with an active interest in human rights and refugee issues. He became an Adjunct Professor at the Australian Catholic University in 2005. He wrote this article in 'The Age', Nov 05, 2009... |

In The National Times, Paul Sheehan wrote an article titled 'Migration: the true story', which was deceptively persuasive. The problem was that, at crucial points, he mis-stated the facts. He began: 'Australia is not a xenophobic nation. The argument is nonsense. Let me count the ways.' He then refers to various aspects of our multi-cultural society. It is true, broadly, that Australia is not racist, but the success of governments and oppositions in whipping up fear and loathing for asylum seekers is, in part, xenophobic. Xenophobia, the fear of strangers, is different from racism. The fact that multiculturalism has succeeded in Australia does not disprove xenophobia. Apart from any other argument, there are Australians who object to our multiculturalism. But in addition, migrants who come to Australia are encouraged to assimilate quickly and they cease to be strangers. By contrast, boat people who are locked away in desert camps or remote islands, who are held behind razor wire, who are treated as a threat to the fabric of our society, are doomed to remain strangers as long as we treat them so. All the evidence points to Australians being xenophobic. He makes the argument that 'People who arrive by boat present a more confronting challenge to legal, security and health screening than those who arrive by air and overstay their visas. Arrivals by air must present valid documentation before travelling.' Arriving without papers makes identity checks more difficult, although the immigration department copes perfectly well. The security aspect of his statement is wrong. ASIO has said repeatedly that no terrorists, or terror suspects, have come to Australia as boat people. They are likely to come by air, on fake papers. Fake papers are probably a much greater threat than no papers, because if a person has no papers they will have to prove who they are. A person on fake papers is simply waved through. Sheehan also argues that 'The rigorous deterrence and screening of unauthorised arrivals is integral to national security. Some of those who have settled in Australia and later engaged in criminal behaviour or welfare fraud have arrived via the refugee or humanitarian programs. ... A recent spate of convictions for terrorist activity within Australia has largely involved people who came as immigrants.' This is dangerous nonsense, because it mixes together two different things: migration and asylum seeking. The security aspect of boat people is a beat-up which ASIO denies. There is no evidence that boat people are more likely to engage in unlawful activity in Australia than any other group If anything, boat-people are under-represented in crime statistics. What Sheehan is arguing is that 'foreigners are more likely to be criminals, asylum seekers are foreigners, so asylum seekers are criminals'. It is obviously bad logic, and has no facts to support it. But then it gets even worse. He says: 'The Sri Lankan high commissioner to Australia, Senaka Walgampaya, said the Tamil Tigers had received significant support from Australia, a view shared by Australian intelligence.' |

Assuming that to be so, there are two things to note. First, the Tamils have been engaged in a struggle for independence. It is not surprising that Tamils the world over have supported their struggle. Second, more relevantly to the present debate, he does not and cannot say that the Tamils in Australia who have supported the Tamil Tigers came here as boat people. His point ceases to be one about boat people. Then Sheehan plays the numbers game, again in a way calculated to mislead readers into a state of panic. He says: 'The number of refugees or displaced persons in the world, more than 20 million, is roughly the same as the population of Australia, 22 million. Advanced economies could only accept all these people by incurring domestic social and economic costs, which they are not prepared to make. Immigration policies have ripple-on effects, hence the need for quotas.' Looking at global refugee flows misses the point that very few of them come here. If numbers are a concern, here are some to consider: Australia's population is 22 million. The number of visitors arriving in Australia each year (for tourism, business etc) is 4.5 million. The number of permanent new immigrants each year is 185,000. The refugee/humanitarian quota per year is 13,500. The number of asylum seekers who come here by air each year is 5000. The number of asylum seekers who have come here by boat this year is 1500, which is equivalent to three days' migration intake. It is hard to understand why anyone can be fussed by an unauthorised boat arrival rate of 1500 per year. Finally, Sheehan comes to his point: 'The 78 ethnic Tamils who have illegally occupied the Australian customs vessel Oceanic Viking are demanding rights that do not exist under international law. Most have been in Indonesia for some time. They want to settle in Australia, or another wealthy country, but that decision is not theirs to make.' Perhaps it is just a quibble, but they have not 'illegally occupied' the Oceanic Viking. They were picked up by it. They were then taken to Indonesia but they do not want to disembark in Indonesia. Why? Because Indonesia has not signed the Refugees Convention, so if these people are forced ashore in Indonesia, they will be locked up indefinitely, even after they are assessed as refugees by the UN High Commission for Refugees. They will be held there without any rights, potentially for 5 to 10 years. Australia will pay to hold them there. At present Australia is paying UNHCR and the International Organisation for Migration to accommodate refugees, who are not permitted by Indonesia to work or to live in the community. It is not too surprising that the 78 Tamils are not keen to be put in jail simply because they don't want to face persecution in Sri Lanka. If some (or even all) of the 78 Tamils have been in Indonesia for some years, the case is plainer. They want freedom. Sheehan says they want to go to 'Australia, or another wealthy country', but what they want is to go to a country where they can be free. That seems a reasonable idea to me. In their position, I would want the same. Wouldn't you? |

| TOP |

The pointed finger

'Many times the priest is not blameless but many times, he is!'

Sister Brenda Herman reflects on the priesthood today in the Facebook of the Missionary Servants of the Most Blessed Trinity (Trinitarian Sisters), Oct 30, 2009... . |

On June 19, 2009 Benedict XVI declared a 'Year for Priests.' This year will conclude with an international gathering of priests in Rome, June 9-11, 2010. Over the journey of my life as a Roman Catholic, I have met, worked with, admired, fought with and loved different priests. I have met them all over the world. I have shared meals with them, listened to their mission stories, met the people to and with whom they minister, and in the past, met the other priests with whom they lived. Today, that is less and less a reality as many priests in the USA live and work alone. For many priests in rural areas of this country, that is probably nothing new. I had the opportunity over the years to meet priests in large gatherings at the Diocesan and national level. I spent a year on a Bernadin Fellowship with Catholic Charities USA interviewing priests across the country, asking them questions about their formation into the social mission of the Church. I learned that majority of priests care deeply about the poor and marginalized. And I also learned that many of them fear preaching about these social issues in a climate where every word is heard by many of the laity as less about the Gospel and more connected to politics or political parties. Today, I am concerned about priests, more than in the past. I am watching them try to regain a sense of self after one of the worst scandals in the history of the Church. I see many of them trying to understand the meaning of their confreres (including Bishops) sexual abuse. I hear them say that they feel ashamed and tainted and are working twice as hard to regain the trust and respect of the laity. And I hear them say that they often lack the support they need to keep going. This lack of support is felt in many different ways and often those who make the role more difficult can include their Bishop. Most of them express hope. They love their people. They love the call to pastor. All with whom I have spoken over the years are clear that they have been formed by the laity. Yes, they may have learned doctrine in the seminary, but they learned to ‘pastor’ from the people. When interviewing the priests about the social mission most said that they had little or no exposure to the social teachings in the seminary but all admitted that the ‘social’ issues were made very clear when they met hungry parishioners, met the dying with no health insurance, |

saw people lose their homes, and saw parents try to feed and care for their children. Said one priest to me, “All the books in the world can never teach you the suffering of the people.You have to be there with them” I realize that there are many people who have suffered in a contact with a priest. I have met people who have left the Church because of something either said or denied. I know that there are priests who today make it very difficult for laity to be part of a loving community. And I wonder about these men as well. I chose to write this short blog simply to get us to think about the priests we have met in our own lives. Most laity and religious feel some ambivalence about the issues facing priests today. Many have said to me that they would never encourage a son to become a priest. Some have jokingly said but they would encourage a daughter! Underneath these responses often lies a deep sense of loss or anger and a struggle to understand the movement of the Holy Spirit within the Church at this time in history. Together, as ordained and laity, we must try to understand ‘the signs of the times’ and together try to discern God’s will. I chose the picture of Jesus as the High Priest being judged by the high priest. The pointed finger, the posture of admonishing Jesus captured what I see today in many Catholics as the priest stands before them. We are more educated. We know that we are the church. We raise our fingers (even our fists) as we confront and try to find answers. Many times the priest is not blameless but many times, he is! Often the anger must be dealt with before we can move ahead. We do not often know how to collaborate with the ordained (nor they with us) to bring about the reign of God in a very troubled and broken world. I pray that this year of the priest brings about a great deal of dialogue among us. I hope that it surfaces all the hurts and happiness. I pray that those who are alienated from the Church because of some hurt (real or imagined) can find a way to dialogue and find peace. I pray for the priests I know and love and all I have met over these years. While I leave the future of the ‘priesthood’ in the hands of God, I also pray for all of those who have responded to this call and who live and work amongst us. |

| TOP |